The stages of type 1 diabetes

Learn the stages of type 1 diabetes and why they're important.

Through decades of research, we know that type 1 diabetes (T1D) starts well before symptoms develop and diagnosis typically occurs. We can use this knowledge to prevent people from developing serious illness at the point of diagnosis, improve their long-term health, and investigate therapies which, in future, could stop T1D in its tracks.

In this article, you’ll learn:

- How T1D starts before you have any symptoms

- The stages of T1D development

- How the stages progress

- Why the pre-symptomatic stages are important

- The JDRF research projects that focus on T1D stages

- Where to read more

⇨ Download this article as a PDF

Type 1 diabetes starts before you have any symptoms

T1D is an autoimmune condition where the immune system mistakenly attacks the beta cells in the pancreas. These cells are responsible for producing insulin, a hormone essential for regulating blood glucose levels. The immune attack results in the gradual loss of beta cells or impacts their function so people with established T1D can no longer produce their own insulin. This means that people with T1D need to inject insulin to control their blood glucose levels for life.

We previously thought that T1D starts shortly before (or when) people show the 4T symptoms: thirst, toilet (frequent urination), thinness and tiredness. But decades of research have discovered that there are several detectable changes in people before these symptoms develop. These changes can occur months or even years before diagnosis typically occurs.

These so called ‘pre-symptomatic stages’ are Stage 1 and Stage 2 T1D. Stage 3 T1D is when diagnosis traditionally occurs after people start showing the 4T symptoms of T1D.

While people in Stage 1 and Stage 2 don’t officially have T1D, being in these stages increases the chance of developing T1D down the track. Clinicians and researchers can take advantage of this information to help those people who are at risk.

The stages of T1D development

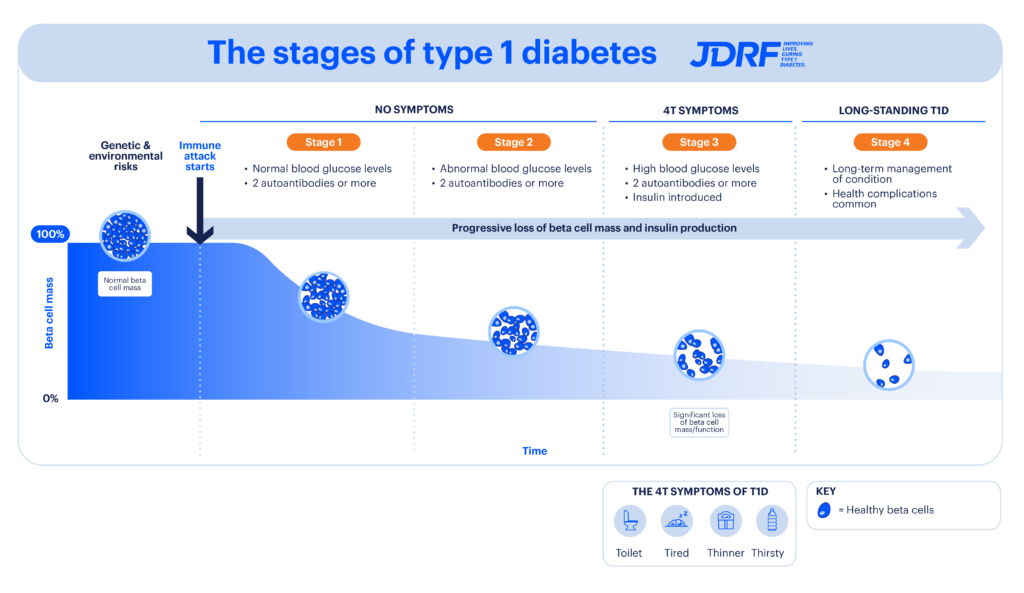

Above image: There are several stages of T1D development, which progress over time. In those who are genetically susceptible, environmental triggers start the body’s immune attack on insulin-producing beta cells. Two or more autoantibodies can be detected in the blood from as early as Stage 1 T1D, and blood glucose levels become more difficult to control as the condition progresses.

– Stages 1 and 2 occur before symptoms are noticed, and before the person knows they’re at risk of developing T1D. At these stages, we can detect two or more autoantibodies in the blood. This is when T1D screening can occur.

– Stage 3 is the time of traditional diagnosis and is the symptomatic period when the 4T symptoms of T1D occur (thirst, tiredness, thinness and toilet [increased urination]).

– Stage 4 is long-standing or established T1D. Each stage is associated with decreasing beta cell mass or function as these cells are incorrectly destroyed by the immune system. This results in less insulin being produced.

Researchers think that some people are genetically susceptible to T1D. In those people, the condition starts when something in the environment triggers the immune attack on the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas.

Researchers – including those involved in the Environmental Determinants of Islet Autoimmunity (ENDIA) study here in Australia – are working hard to unveil what these environmental triggers may be. For example, there’s strong evidence that a family of viruses called enteroviruses are associated with T1D development, and part of the ENDIA study is looking to further identify these. Learn more about ENDIA in Case Study 2 in our impact report.

So how do researchers know if someone is in the early stages of T1D? When there’s an immune attack against pancreatic beta cells, the body produces proteins called autoantibodies. These autoantibodies can be detected in blood.

There are several T1D autoantibodies we know of. Someone in all stages of T1D may have the following autoantibodies in their blood.

- IA-2A: insulinoma-associated protein 2 autoantibody

- IAA: insulin autoantibodies

- ICA: islet cell autoantibodies

- GAD-65: glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 autoantibody

- ZnT8: zinc transporter 8 autoantibody

While these antibodies can appear in any order, their number and persistence can predict if someone will go on to develop the condition. For example, people who have two or more persistent autoantibodies have a 70% chance of developing T1D in the next 10 years, and nearly 100% chance of developing T1D in their lifetime. This means that nearly all people with two or more autoantibodies will go on to develop T1D in the future.

How T1D stages progress

In people who are genetically susceptible to the condition, environmental factors (such as viral infections) trigger the body’s own immune system to attack beta cells. Autoantibodies are produced, and these can be detected in blood through a blood test.

Two or more autoantibodies are detected in the blood, but the person still has normal blood glucose levels. The immune attack results in healthy beta cells being destroyed and beta cell mass falling. There are no obvious symptoms at this time.

Two or more autoantibodies are detected in the blood. The person’s blood glucose levels become harder to control, with abnormal changes. Beta cell loss continues.

The person exhibits the 4T symptoms of T1D as a result of high blood glucose levels. This is the stage where traditional diagnosis occurs. By this stage, the immune attack has resulted in a significant loss of beta cell mass and function, and not enough insulin is produced to maintain blood glucose levels in a normal range. The person usually starts insulin treatment. Two or more autoantibodies are still detected in the blood.

The person has long-standing T1D after living with the condition for numerous years and is insulin dependent. Long-term health complications are common. Two or more autoantibodies may or may not be detected in the blood.

Why are the pre-symptomatic stages important?

We now have the technology to easily detect if someone is in Stage 1 or 2 of T1D. This is done with a simple blood test that detects the presence of autoantibodies. Knowing whether someone is in the pre-symptomatic stages of T1D is beneficial for several reasons.

Screening for T1D risk

By detecting autoantibodies in the blood, we can determine the chance of someone going on to develop T1D. If this chance is high, the person can be monitored by health services and reduce the shock of diagnosis.

Importantly, we know that screening, combined with health follow-ups and education, can significantly reduce the rate of developing a dangerous condition called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) when diagnosed. In fact, it has been shown that T1D screening and health follow-up reduces rates of DKA at diagnosis by 90%.

DKA occurs when low levels of insulin and high blood glucose levels result in acidic ketones in the blood. Left untreated, DKA can be fatal. DKA at diagnosis is also associated with worse long-term health effects, so preventing it from happening is important.

Screening can also allow people at high risk of developing T1D to enter clinical trials looking to delay the progression to Stage 3 T1D.

New therapies for T1D

There are currently a lot of research projects that are looking at drugs called ‘disease modifying therapies’. Researchers aim to use these drugs to halt T1D progression or prevent it in the first place. Many of these focus on preventing people from moving from Stage 2 to Stage 3 T1D, essentially stopping T1D in its tracks. Identifying people in these pre-symptomatic stages is essential if they’d like to access clinical trials testing these therapies or use these therapies in the future as they become available.

One such disease modifying therapy, called Teplizumab, has already been approved in the US to prevent progression from Stage 2 to 3 T1D in those aged eight years and older. Many other drugs are at the clinical trial stage, and rapid progress is being made to identify which ones can prevent symptomatic T1D from taking hold. Other drugs, like baricitinib, might one day be used to stop the progression of T1D in those newly diagnosed. In the future, these may be able to halt the progression from Stage 3 to 4. Research is ongoing.

Causes of T1D and prevention

By studying people who develop pre-symptomatic T1D, we may be able to identify which environmental events are associated with the start of T1D. In this way, we’ll be able to further understand the causes of T1D and, in turn, develop preventive strategies for genetically susceptible people. These might one day include things like vaccines and nutritional interventions.

JDRF leads the way in research that focuses on T1D stages

JDRF is committed to a world without T1D. That’s why we fund research which will ultimately prevent people from reaching clinical T1D (Stage 3 T1D).

Specifically, JDRF Australia is funding the following research projects under our T1D Clinical Research Network (T1DCRN):

- Screening for T1D: the Australian Type 1 Diabetes National Screening Pilot aims to identify the best T1D screening method for Australia by screening 9,000 children and infants for the presence of autoantibodies. This will indicate if they’re in the early stages of T1D and then connect their family to a healthcare team. While we know that T1D can run in families, nine out of 10 people diagnosed with it have no family history of the condition. This is why a screening of the general population is important. We also fund Type1Screen, which screens for autoantibodies in the family members of people with T1D.

- New therapies to slow T1D progression: JDRF heavily invests in clinical trials which test disease modifying therapies, drugs to slow down T1D progression across the different stages. We’ve established the Australasian Type 1 Diabetes Immunotherapy Collaborative (ATIC), which allows the testing of disease modifying therapies that target the immune system attack seen T1D. For example, JDRF funding led to breakthrough results showing that baricitinib can delay the progression of T1D in those newly diagnosed. Other clinical trials are planned for the future.

Learn how you can participate in clinical trials and studies.

Our research portfolio

Groundbreaking projects like these are only possible with support from our community. The future of 130,000 Australians living with T1D and the eight more diagnosed each day depends on it.

To get involved, donate here.

Explore all the research projects funded by JDRF Australia.

⇨ Download this article as a PDF

Further reading

- Disease-Modifying Therapies in Type 1 Diabetes: A Look into the Future of Diabetes Practice

- Stages of Type 1 Diabetes and Mechanism of Action of Teplizumab

- Staging Presymptomatic Type 1 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association

- T1Detect: Learn About Type 1 Diabetes Risk Screening

- Type1 Diabetes TrialNet