100 years ago, a type 1 diabetes diagnosis was terminal – learn how far we’ve come

Before 1921, a type 1 diabetes diagnosis was terminal. It spelt a death sentence with few effective treatments.

2022 marked 100 years since a few Canadian scientists successfully administered insulin to a human patient… but how did we get here? If you had T1D, you were likely put on one of many strict, fad diets.

1886

Bernhard Naunyn, one of the biggest early driving forces for the emerging understanding of T1D, locked his patients in a room for 5 months to achieve “sugar-freedom”. If sugar-freedom was unattainable by eliminating carbohydrates, he moved on to reduce calories and protein in the diet of his patients.

1904

There was the oat-cure. Coined by Professor Carl van Noorden, the oat-cure involved eating a mixture of oat flour, butter and vegetable albumin every 2 hours for one to two weeks, before gradually returning to a more varied diet. At the time, the oat-cure was thought to be the best means at their disposal to combat DKA and avert diabetic coma.

1919

Frederick M. Allen from the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research advocated fasting for 2-10 days, followed by a restricted calorie diet consisting of mainly fat and protein. Carbohydrates only featured in amounts necessary to keep the patient alive. If diabetes symptoms reappeared, it was back to fasting for these patients – essentially starving them to manage the disease. Some patients did indeed starve to death.

Even following one of these diets, people with type 1 diabetes could only expect to live for about a year after diagnosis.

We’ve come a long way since those days. People diagnosed with type 1 diabetes now can expect to live a long and fulfilling life with proper management – all thanks to a few pioneers.

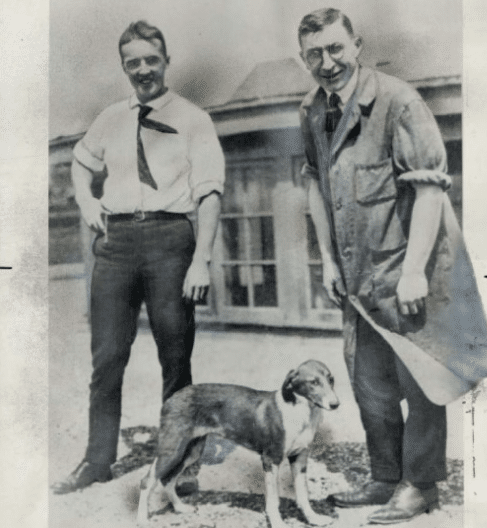

Image source: UMass Medical School

In the summer of 1921 at the University of Toronto, Doctors Frederick Banting and Charles Best achieved a huge breakthrough. The Canadians managed to successfully isolate insulin from canine test subjects.

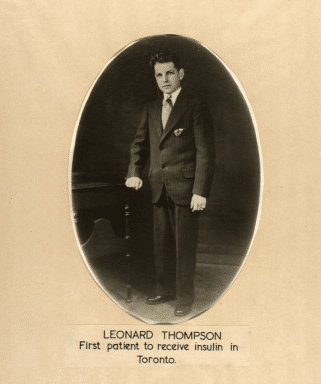

A mere 6 months later, insulin was administered to the first ever human patient: Leonard Thompson.

Image source: UMass Medical School

Fourteen-year-old Leonard Thompson became the first human with type 1 diabetes to receive an insulin injection on 11 January 1922. At the time, Leonard was 5’11”, weighed just 29kgs and had been drifting in and out of a diabetic coma at Toronto General Hospital. He’d been carried into hospital by his father, and his daily dietary intake had been reduced to just 450 calories.

While the first, impure form of insulin failed to improve his condition, a subsequent version administered on 23 January 1922 helped restore his blood glucose levels back to normal and alleviate his symptoms. This more concentrated version was extracted by Dr. James Collip.

The effect was noticed immediately. According to Banting’s very own records “the boy became brighter, more active, looked better and said he felt stronger.”

Leonard Thompson lived another 13 years using insulin. Unfortunately, at just 27-years-old, Leonard passed away due to pneumonia, which was thought to be a complication of his diabetes.

100 years on

Last year marked 100 years since that fateful day when Banting and Best successfully administered insulin to Leonard Thompson. The impact of insulin on the lives of millions around the world – from Leonard in 1922 to the more than 130,000 Australians living with type 1 diabetes each day today – has been immeasurable.

JDRF has been part of every breakthrough in T1D care for the last 40 years. Yet over 100 years on, insulin remains the only treatment option. This means the needles, injections, finger pricks, bulky devices and constant monitoring remain part of our lives.

We’re acknowledging this significant milestone and renewing our commitment to moving, and eventually removing the needle for T1D. Let’s make type 1 diabetes a memory, not a milestone.